America’s Asymmetric Politics

What political science teaches (and doesn’t teach) about Republicans and Democrats

This semester I’m teaching my first political science class since becoming a senior lecturer at Penn. It’s on the Republican primaries—using the candidates running and their relative polling positions as a lens through which to understand the character of the GOP as a party.

We’ll be reading a fair amount of history and journalism in the class, but also (as you might expect) empirical political science. This week’s reading is the latter—a very good book by political scientists Matt Grossmann and David A. Hopkins called Asymmetric Politics: Ideological Republicans and Group Interest Democrats. The book’s thesis is telegraphed in its subtitle. The authors argue (using a range of evidence, much of it rooted in public opinion research) that the Democratic Party is really a coalition of interest groups, while the Republicans “can be most accurately characterized as the vehicle of an ideological movement.”

I think this is an extremely useful and largely accurate way of distinguishing between the two parties—or at least that it was at the time the book was published, in 2016. As I say, the authors marshal a lot of evidence in its favor. More Republicans describe themselves as conservatives than Democrats describe themselves as liberals or progressives. There are more conservative and moderate Dems than there are liberal and moderate Republicans. Republicans are more likely than Democrats to value ideological purity over moderation and pragmatism. And so forth.

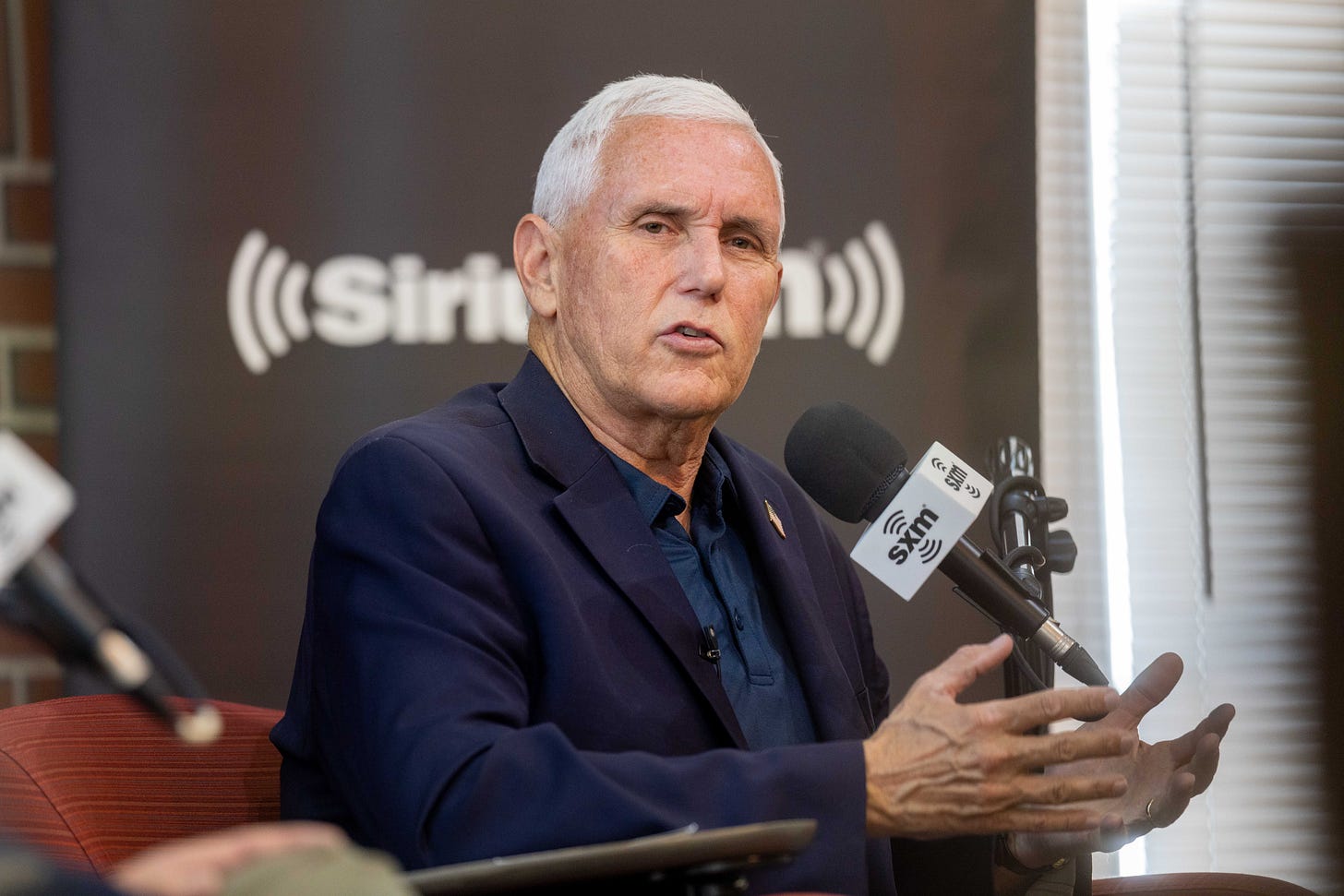

I think all of that is true at the level of broad generalization. Or rather, that it was true up to the year in which the book appeared. But as you may have heard, big things have been happening in American politics since that time. The Reaganite ideology Grossmann and Hopkins describe as the animating force within the Republican Party suffered a body blow from Donald Trump’s right-wing populism during the GOP primaries in 2016, and in the years since it has been, if not supplanted entirely, then at least radically transformed. (Mike Pence’s speech on Wednesday of this week was a strong statement of opposition to this transformation, marred only by the fact that it comes too late, after the transformation effectuated by the president he served loyally for four years is largely complete.)

But what is the character of this transformation? Has the Republican Party replaced one ideology (conservatism) with another (populism)? Or has it stopped relying on ideology for cohesion and mobilization, replacing them with something else that serves those functions? And what about the Democratic Party? Is it still the coalition of jostling interest groups Grossmann and Hopkins claimed it was a little less than a decade ago? Or has it begun to embrace a holistic ideology of its own?

The Republican Metamorphosis

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Notes from the Middleground to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.