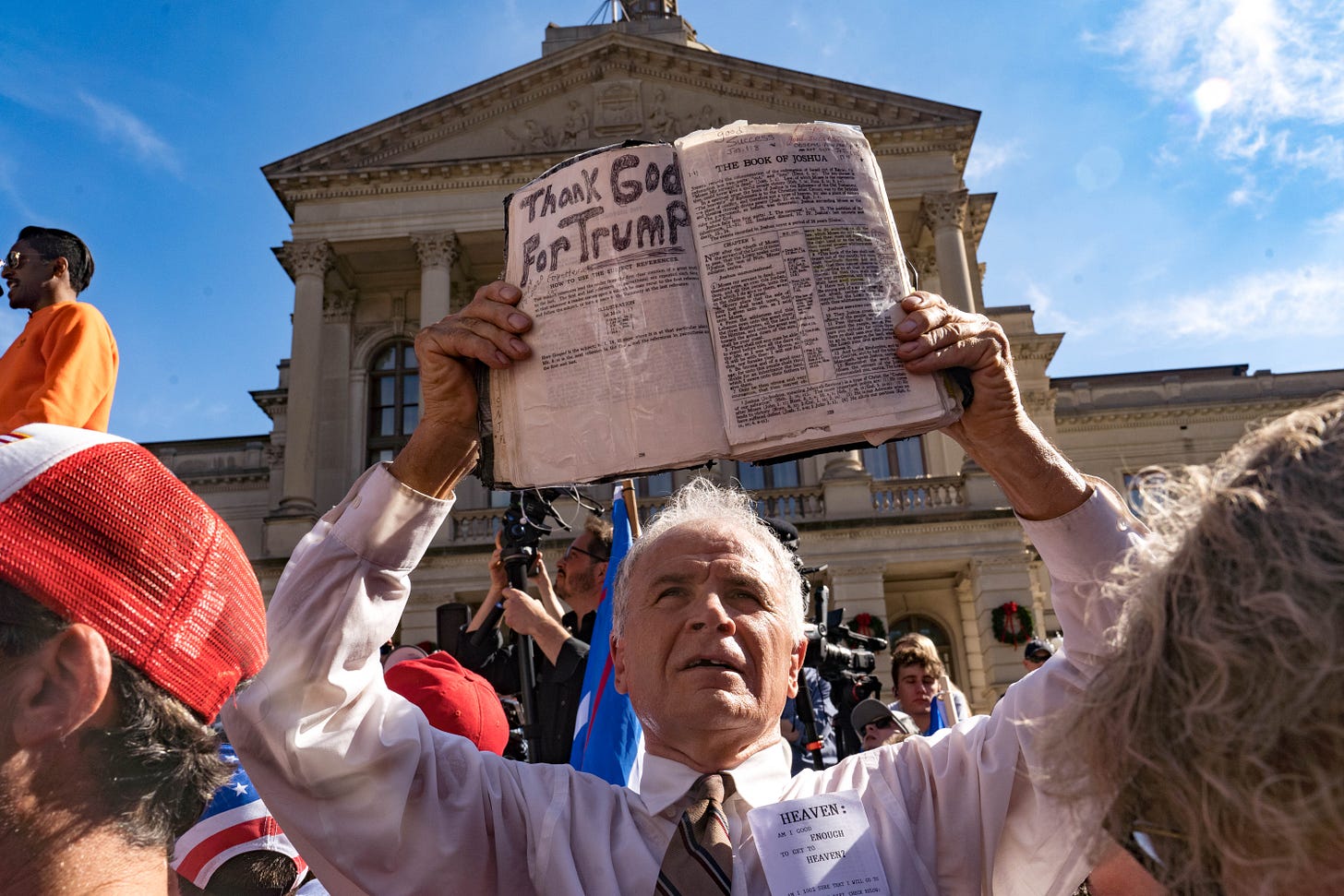

How the Religious Right Lost While Winning

Once a junior partner, always a junior partner

I’m a little famous (or perhaps a little infamous) for raising alarms about the religious right during its peak of political power and influence in George W. Bush’s Washington. So I took special note when conservative pundit Ross Douthat tweeted out the following comment in the midst of Donald Trump’s hostile takeover of the Republican Party roughly a decade later:

It’s a great line, but was Douthat correct about what was coming? Is it really accurate to say the four years of the Trump administration marked the advent of a post-religious right? How could that be, when the president went out of his way on a daily basis to antagonize the enemies of the religious right and ended up appointing the three staunchly conservative Supreme Court justices who have now made it possible to overturn Roe v. Wade, fulfilling a 49-year goal for opponents of abortion, many of whom are motivated by religious faith?

I do think Douthat’s comment has been vindicated—but it’s a complicated story.

Republican Class Warfare

As National Review’s Nate Hochman explains in a long, must-read op-ed in the New York Times provocatively titled, “What Comes After the Religious Right?,” the United States is rapidly secularizing, and so is the Republican electorate. This process was hastened by Trump’s campaign for president, which appealed most powerfully to the least religious segment of the GOP, as well as to a good number of secular independents.

The result, six years later, is a Republican Party much more organized around class and regional resentments than religious passions and aspirations. Those resentments unify the different factions of the GOP in opposition to the highly educated urban professionals and activists who dominate the public face of the Democratic Party. A similar process is unfolding in countries across the democratic world, with secular right-wing parties mobilizing along class and regional lines against left-leaning elites.

But what about the religious voters who used to form the activist core of the Republican Party? Even if they now make up a smaller portion of the GOP, aren’t they still somehow running the show on the right?

The truth is that they never really have. Instead, the religious right is shifting from being one kind of junior partner in the GOP’s electoral coalition to being a different kind of junior partner. Whether this religious faction of the Republican Party will be satisfied with that status will depend on what its members really want—and that has been unclear for a long time.

The Two Religious Rights

Back when I was a nominal member of the religious right myself, working at First Things from 2001 to 2005, I often struggled to grasp what my own magazine was after. When I first took the job, I thought the goal was to secure a seat at the table of public discussion and policymaking for people whose moral convictions were grounded in and flowed from religious conviction. That seemed like an aim compatible with classical liberalism—and indeed, the magazine’s highly influential founder (Richard John Neuhaus) often wrote and spoke of his project as an expression of liberalism, rightly understood.

Yet there were also times when the magazine and its leading writers seemed to crave greater power—not just a seat at the table, but control of the table. They aimed to baptize the polity, read the Constitution through the lens of papal encyclicals, and use state power to enforce the moral convictions of the most pious members of the American electorate, with less religious and unreligious Americans relegated to the status of second-class citizens.

The more modest religious right came to the fore when its members felt secure in their political influence, with invitations to prominent seats at the table coming from the president himself. The nastier side emerged at moments of anger, despair, and disappointment.

The most notorious example came in the “End of Democracy?” symposium published in the issue of the magazine dated November 1996, the month of Bill Clinton’s re-election to the White House. Back then, the religious right still considered itself America’s moral majority, so the prospect of repeatedly losing out to secular liberalism in the political arena seemed to point toward a collapse of democracy itself—and the possible need for a revolution to restore the righteous to their rightful place of power.

From Moral Majority to Moral Minority

By the time Donald Trump launched his campaign for the presidency in the summer of 2015, things looked very different. Eight years of the Bush administration had delivered relatively little for the religious right, whose leaders began to wonder whether they were being taken for granted, with the movement’s voters expected to show up on Election Day so Republicans could win power then use it to do the bidding of other factions in the party and conservative movement. And, of course, living through two terms of the Obama administration, which included the stunning defeat of the Obergefell Supreme Court decision declaring gay marriage a constitutional right, was far worse.

That’s when Trump made the demoralized religious right an offer it couldn’t refuse. It was an offer tailor made for a faction feeling weaker and more vulnerable than ever and yet still longing for concrete victories. The religious right would have to give up all hope of taking over the table. Secularism wouldn’t be stopped or pushed back. Porn wouldn’t be banned. No-fault divorce wouldn’t be done away with. Gay marriage wouldn’t be abolished.

But more conservative judges than ever would be appointed. Republican officeholders and candidates would be far more aggressive in pushing back against efforts by the federal bureaucracy to shift the country to the left on cultural questions. And instead of trying to build an electoral majority and governing agenda on the basis of a watery remnant of moral traditionalism shared by shrinking numbers of religious believers, everyone furious about the arrogance and condescension of liberal and progressive elites would come together to give them a collective kick in the teeth.

All the religious right would have to do is be willing to vote for and work with a president who exemplified the very things they had long detested about post-1960s, secular America. It would be a deal with the devil, but it could deliver in a way earlier deals with well-meaning, sincere, but ultimately impotent politicians never did. Instead of being taken for granted and soothed by edifying words, now the religious right would be given the equivalent of a binding contract: Vote for me, and I will fight for you, relentlessly, even if I couldn’t personally care less about what you care about and believe.

The religious right paid its protection money, and its members got the hit they bargained for in the form of the imminent overturning of Roe.

The Religious Right in a Secularizing Age

But will that be enough? I don’t mean in the sense that what remains of the religious right might long for policy victories that go beyond gutting abortion rights. (That’s bound to happen.) I’m talking, instead, about whether what remains of the religious right will be willing to accept that it is, and is almost certain to remain, a minority within an ever-more-secular GOP and conservative movement, let alone within an ever-more-secular United States as a whole?

Clearly the activists who dream of banning abortion at the federal level, outlawing contraception, and eliminating gay marriage seem to have much more ambitious plans—as do the “integralist” Catholic writers who fantasize about pious Christians using government power to impose their vision of the Highest Good on a grateful nation. Neither seems reconciled to being junior partners in a coalition led by trash-talking, theologically indifferent “barstool conservatives.”

Activists and intellectuals don’t command that many votes. But they sure can make things difficult for a party striving to win electoral majorities. (Just ask the Democrats.) For that reason, the Republican Party’s greatest struggles with the religious right may still lie ahead.