Eulogies invariably begin by listing some of the most admirable qualities of the person who has died. In this case, doing so is easy.

Irwin Linker, the child of Jewish immigrants from Poland and Austria, was raised in a poor (though not destitute) family in the Bronx. He was smart enough as an early adolescent to pass the formidable entrance exam to Stuyvesant High School, and he had enough ambition to travel on the subway well over an hour each way, every day, to the imposing school down on East 15th St. in Manhattan.

He was extremely creative, aspiring by his late teens to be a musician, cutting demos performing songs he’d composed on the piano. Later on, he turned to graphic design and painting. This never stopped, in his career as a creative director for a number of commercial magazines, including an extended period working with Stan Lee at Marvel Comics, and as a hobby. He would often say, “If you can be creative, you’ll never be bored.” Irwin never complained of being bored.

He was an incisive critic—of the visual arts, of film, of music, and of human beings. He was a master of sizing up people and situations in an instant, with a lacerating sense of humor and perfect comic timing, and it was eerie how accurate he could be. He never cared about other people’s opinions if they clashed with his own. He rendered subjective judgments with the confident authority of a scientist recording an objective fact. I’ve said on many occasions that he gave me an excellent apprenticeship in intellectual independence.

Finally, Irwin was incredibly passionate about his loves, including his love for his grandkids, whom he would invariably praise to the skies immediately following every visit with them, telling me how delightful they are, how spectacular their futures would be, and what an outstanding job their mother and I were doing as parents. (I told you he had excellent judgment.)

He also loved life very deeply—not the past, talk of which would usually elicit scorn; but the average-everyday joys and pleasures of the present; and the future, seen always through overflowing hopes for ever-greater achievements. The poet Dylan Thomas would surely have admired how Irwin refused to go gentle into that good night. And let me tell you, if you doubt that he raged, raged against the dying of the light, just ask some of the nurses, aides, and social workers who cared for Irwin at Caleb Hitchcock Health Center and Masonicare over the past 15 months.

But like many Jews who came of age in the demonic shadow of the Holocaust—Irwin was 6 in 1945—he also had a fatalistic side. He was prone to proclaiming after bad news, “Man plans, fate laughs.” But it wasn’t just the looming horror of the Holocaust that made him this way. He also had, for very personal reasons, a self-protective side. He went through life as if tending to and guarding “a wound that will never heal,” to quote a Tom Waits song Irwin loved. He didn’t let a lot of people get close. He had trouble trusting. He could also be a little scary, and he liked it that way. It was another way of protecting himself.

That tendency toward intimidation was one of many things linking him to Jack Nicholson, one of his favorite actors. He looked a little like Jack, but Irwin also resembled him in the swaggeringly self-confident way he carried himself. Both forms of likeness were clearly at play when, several years ago, he sauntered into a restaurant and the maître d’ pointed at him and proclaimed, “Jack Nicholson!” Without missing a beat, Dad pointed right back and barked, “You can’t handle the truth!”

But the connection to Jack runs even deeper than that.

About six weeks ago, in what turned out to be our last real conversation, I mentioned that Bob Rafelson, the director of the film Five Easy Pieces, had died, and Dad pronounced it his favorite movie. I don’t know if that was always true. I’d heard him say the same about a handful of other films down through the years. But the effusive praise of Five Easy Pieces in the final weeks of his life is telling, I think.

For those who don’t know the 1970 film, it stars the young Nicholson as a man who spends his life running away from his past, his family, and his friends and lovers, opting for repeated acts of self-erasure. He’s a quintessential anti-hero, consumed by self-loathing, denying his talents, and living his life in flight from anyone who tries to love him, settling for odd jobs and then bolting for the door the moment the prospect of permanence begins to threaten him. The film is one of the most heartbreaking character studies I’ve ever seen.

I’m convinced that Dad saw something of himself in this terribly unhappy, haunted character—and I understand why. Yet it’s also the case that in the decisive respect Irwin was nothing at all like the film’s protagonist, as he demonstrated in what I think he would agree was the most significant moment of his life.

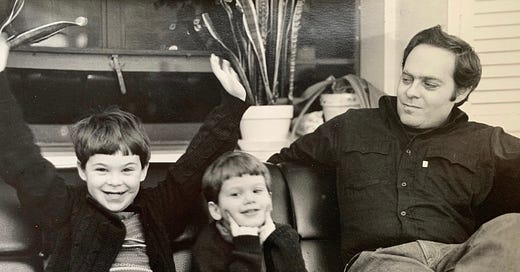

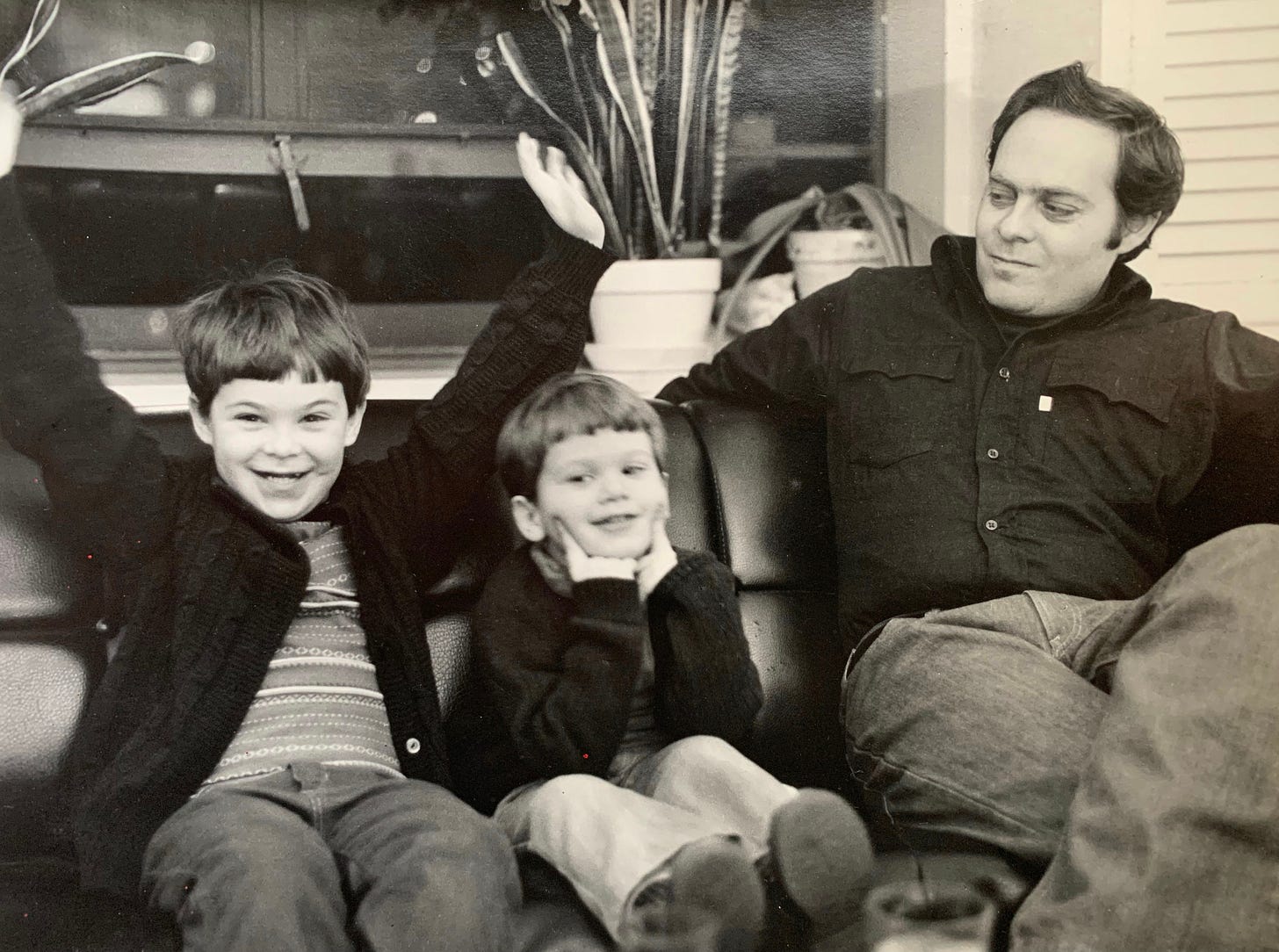

That’s when the 38-year-old Irwin moved with his wife and two young boys—aged 8 and 5—from an apartment in New York City to a house 50 miles away in suburban Fairfield, Connecticut, only to have his marriage utterly collapse over the following four short months.

None of us ever really understood what led his wife—our mother—to suffer a mental breakdown that drove her to emotionally abuse all three of us with ferocious cruelty and then abandon us. But that’s exactly what she did, regardless of whether it made any sense. My brother and I saw her a handful of times in the year after she moved out and relinquished custody. Two letters arrived from the other side of the country over the next couple of years. And then she vanished entirely.

Think of it. It’s 1978, when mothers nearly always received primary custody after divorce. Irwin has never lived anywhere but an apartment where it’s possible to call a super when something breaks down or goes wrong. The house is half furnished. His job is an 80-minute train ride away. He knows no one within a 40-mile radius, and barely even knows his way around the town where he must figure out how to raise his two young, traumatized children, utterly alone.

You’d think he’d have remarried in record time, grabbing the first woman he could find, out of the desperate need for help. But he didn’t. Not in 1979. Not ever. Instead, he did it entirely on his own.

Down through the years, especially after having my own children, I’ve often marveled at it. How terrified and trapped he must have felt, staring at the ceiling in bed at night or sitting on the Metro North train commuting into work, wondering how he could possibly manage it. He must have fantasized about fleeing—of dropping us off with some extended family member so he could get back to living the kind of life he set out to lead as a young man, an aspiring musician and artist, a life that must have looked so very different than this … mess he was now in. It takes far less for Jack Nicholson’s character to head for the hills in Five Easy Pieces.

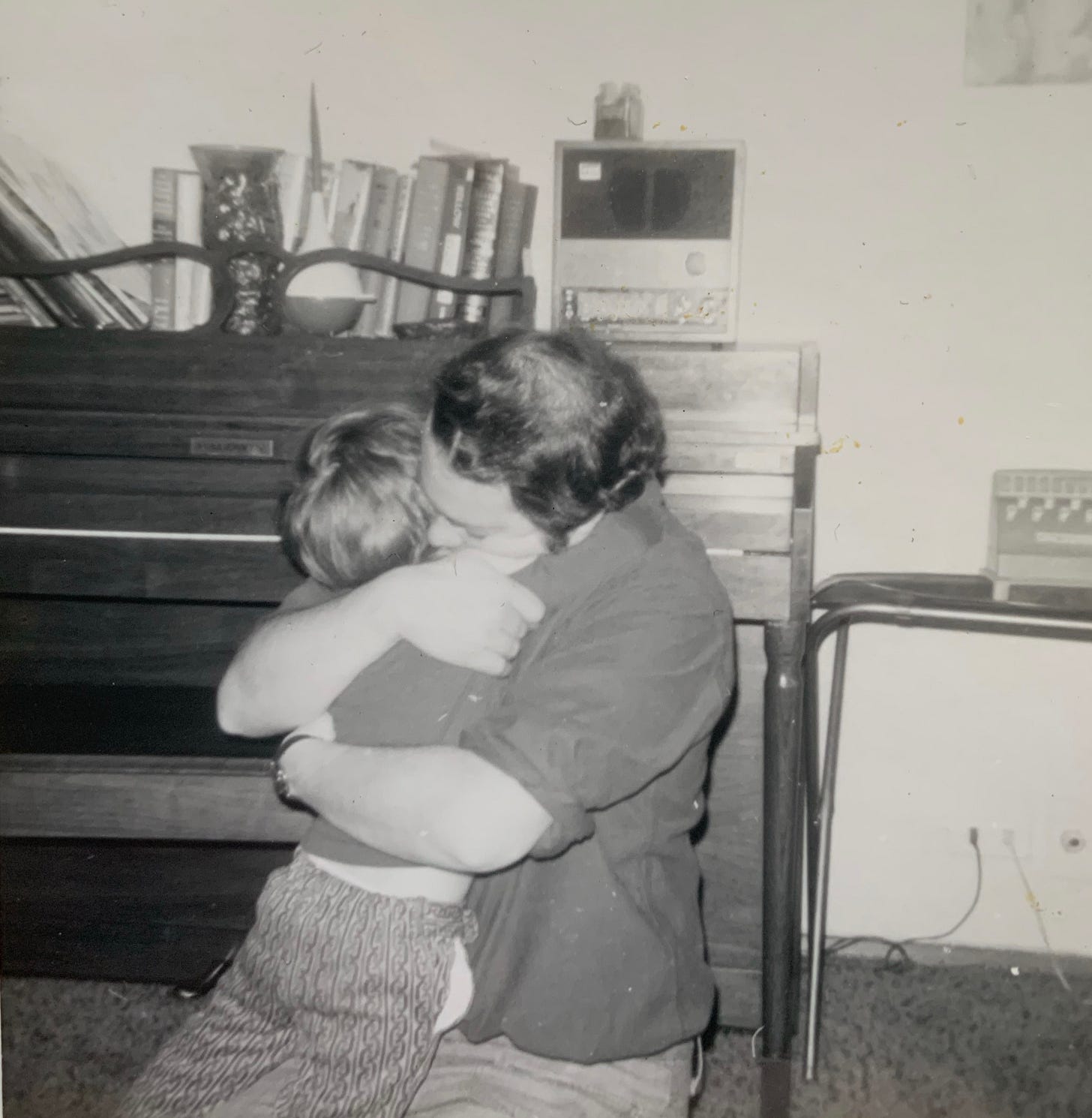

Unlike him, Dad stayed where he was. He figured it out as best he could—sometimes making, I’ll be honest, some … questionable parental decisions! But always giving me and my younger brother the thing we needed more than anything else—the thing every child needs, but especially children who have been hurt so deeply, left with their own wounds that will never fully heal—and that is love. And presence—a person we could count on, who would be there, day-in and day-out, every morning before school, every night at bedtime, through the successes and failures, the bad dreams at 2am, the illnesses, and the joys and the laughter and the anger and the tears.

Irwin sometimes struggled with loving, and even more so with allowing himself to be loved and cared for. But I never once doubted that he loved me and my dear brother with an inextinguishable love. In loving us so fiercely, he gave us a powerful example of how we, too, could love, despite the excruciating pain we had suffered at such a young age. Over the past 18 or so months, during Irwin’s final decline, we finally got to pay a little of it back. It could never have been any other way.

It’s a sentimental cliché to close a eulogy for a parent by saying something like, “I couldn’t have done it without you.” But in this case, it really is true: Dad, I owe you more than I can possibly say. Thank you for being there, for sticking around, and for enacting all the love in your heart for us both.

So very sorry for your loss; your father Irwin was a wonderful man.

Ps: my late father was also Erwin but with an "e".

He appears to have been a good man and a great father. May his memory be a blessing.