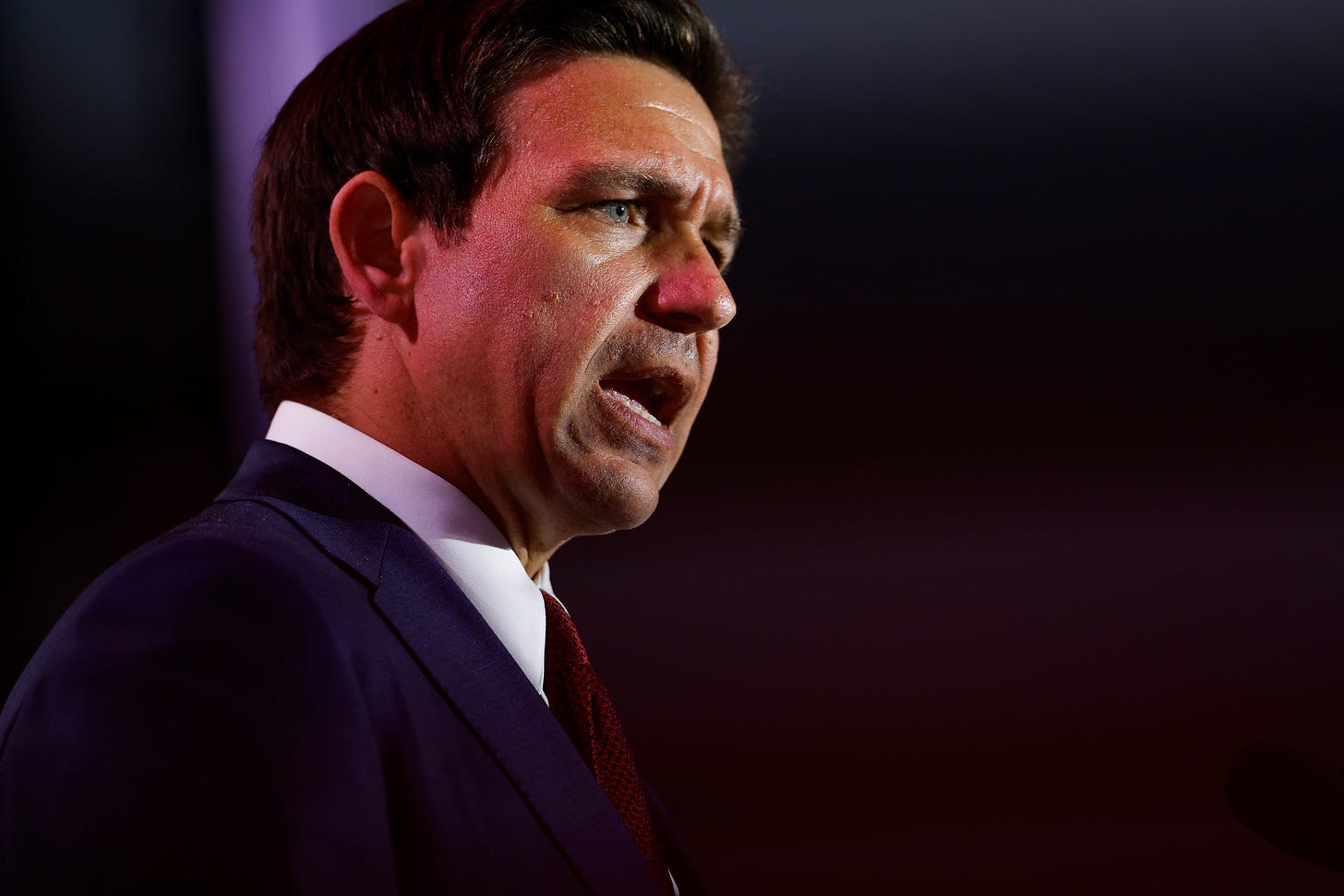

Ron DeSantis, Reactionary Tryhard

On the rise of the counter-revolutionary right

Brief Announcement: I’ll be writing two posts next week. Hopefully today’s will provide you with plenty to chew on between now and Tuesday.

I’ve distinguished before between conservative and reactionary styles of right-leaning politics. But I don’t think pundits and scholars take adequate care in separating them out in either the present or the past. So I want to devote today’s post to doing exactly that—and using the distinction to help us understand what’s happening in and around Ron DeSantis’ flailing presidential campaign, which ran into some messy personnel problems this week involving both a staffer and the candidate himself.

The Core of Conservatism

The way I usually distinguish reactionary politics from conservatism is to say that the latter takes up elements in our world (traditions, habits, ideals, norms, laws) that are inherited from the past, seeks to conserve them in the present, and then hands them down to the future. As I put it in a column I wrote in the fall of 2016 titled “A Requiem for American Conservatism,” a conservative emphasizes and valorizes “forms and formality, order, modesty, nobility, moral rectitude, private and public honor, and steadfast adherence to standards of right conduct and traditional restraints.”

The occasion for this column was, of course, the Republican Party’s embrace of Donald Trump in his general-election contest against Democrat Hillary Clinton. In order to contrast conservatism with the style of politics Trump practiced and demanded from Republicans, I told a brief story about my experience at a dinner of conservative writers and intellectuals in 1999, shortly after Clinton’s husband managed to survive the first presidential impeachment in over 130 years.

There was genuine sorrow in the room, mainly about what Clinton had done to debase the office of the presidency. Everyone sitting around the table worried about young people, in many cases their own children, growing up in a world in which the married president of the United States had engaged in such sordid acts with a much-younger intern in the Oval Office and lied about it under oath—and in which all of the scummy details had been publicized for all to hear and know. It was a moment, they thought, of national disgrace.

I was an imperfect conservative even then, and so I didn’t fully share in this expression of despair. (I hadn’t rallied to Clinton’s defense, but I was relieved the impeachment had failed to remove him from office.) But I nonetheless admired and respected the moral seriousness of my dinner companions, and recognized it as the core of what it means to be conservative.

They believed in high standards, strove to live up to them in their own lives, and felt genuine disgust and dejection when they witnessed their country’s noblest institutions degraded by ignoble behavior. That, for me, will always be the core of conservatism. Not support for limited government or tax cuts. Not favoring open markets. Not fighting for higher defense budgets. But standing for a politics conducted in an elevated key, emphasizing virtue, honor, moral rectitude, earnestness, devotion to principle and integrity, deference toward received authorities and traditions—and speaking of these ideals without irony or shame.

The Reactionary Sensibility

A reactionary, by contrast, is someone who thinks the world has already broken and diverged so radically from the traditions, habits, ideals, norms, and laws that prevailed in the past that the present is a wasteland with nothing worth conserving and handing down. In that case, what’s needed is not greater respect and reverence for the past but rather a radical break from it that amounts to active destruction of the corrupted present before something new and worthwhile can be built in its place. Friedrich Nietzsche expressed this reactionary view quite memorably when he mocked conservatives for their impotent backward glances and insisted, instead, that regeneration demands we “go forward—step by step further into decadence.” (Twilight of the Idols, “Skirmishes of an Untimely Man,” Aphorism 43)

In an important essay written in 1998, and in a subsequent book, my teacher and friend Mark Lilla has suggested a related but alternative way of understanding the distinctiveness of the reactionary outlook—one derived from the successive revolutionary convulsions and backlashes that rocked French politics beginning in 1789 and continuing throughout the 19th century. Viewed in this way, a conservative is someone who emphasizes continuity between the present and the past, and therefore sees moral and political commonality across time and underlying the very real changes that take place throughout history. A reactionary, meanwhile, has his eyes focused on perceived moral discontinuities in history. He lives on the lookout for ruptures, fissures, and revolutions that have torn time itself asunder, separated into a Before and an After. There can be no going back, at least not directly, from the present. What we need first is a counter-revolution to turn back the tide and tear down the world that has emerged from the revolutionary exertions of morality’s mortal enemies.

Reactionaries tend not to see conservatives as mild-mannered allies in this counter-revolutionary program. On the contrary, they view conservatives as saps, suckers, and chumps who end up serving as handmaidens to the revolutionaries, following along behind them, urging conciliation and resignation to change. Conservatives are therefore a major part of the problem, not the solution. The point is to win, to wield ruthless, brute power like their revolutionary enemies do, though for contrary moral ends.

The Career of Reactionary Republicans

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Notes from the Middleground to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.