Stuck in a Moment We Can’t Get Out Of

What the awful Republican debate teaches us about our interminable post-Reaganite interregnum

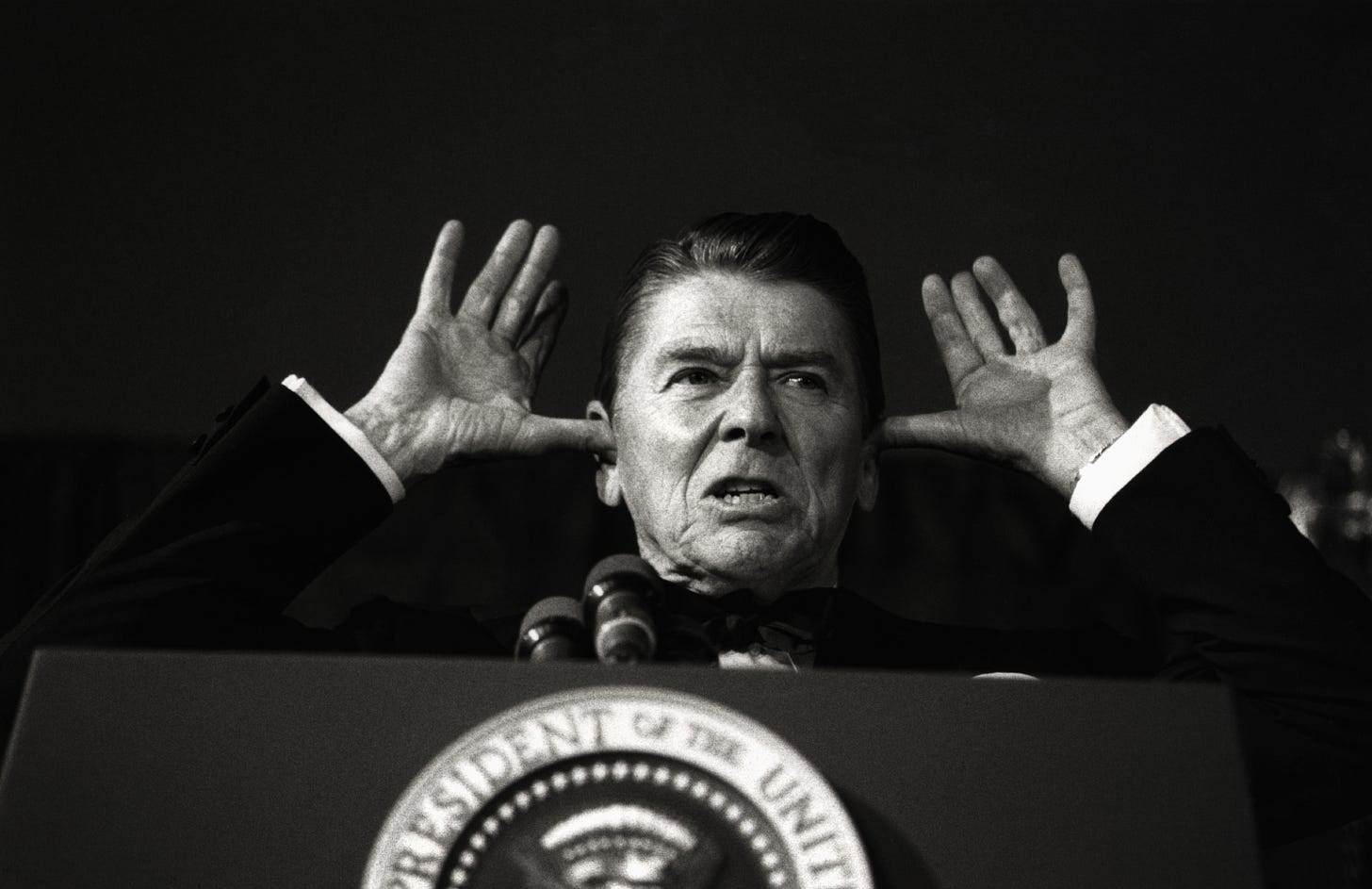

In class on Wednesday afternoon, I showed my students Ronald Reagan’s first inaugural address, delivered nearly 43 years ago. It was a fitting backdrop to the demoralizing experience of watching the second Republican debate at the Reagan Library a few hours later.

Reaganism and the 36-Year Rule

Our class puts Reagan’s victory and vision for America in context—or rather, in several contexts. The Republican Party had been struggling mightily to respond to the confident liberalism of the Democrats since 1932. Dethroning that liberalism was a two-stage process. First, there was the “Southern strategy” made possible by the Democratic Party’s wholly admirable championing of the cause of civil rights. In finally smashing Jim Crow, the party antagonized a sizable bloc of its own voters, who first shifted over to supporting George Wallace’s right-populist third party bid for president in 1968—and then, four years later, moved over to voting for Richard Nixon’s reelection campaign.

Had it not been for Watergate, which left Nixon’s presidency a shattered wreck less than two years after his massive landslide victory against George McGovern in 1972, the Republican Party might have consolidated its new majority and held it for a generation. Instead, we got two years of Gerald Ford followed by four hapless years of Jimmy Carter—as Saigon fell, gas lines circled around the block, crime spiked, hostages were taken in Tehran, and inflation and interest rates surged into double digits.

Those are the contexts for Reagan’s defeat of Carter and reconstitution of the electoral coalition Nixon’s reelection campaign first assembled eight years earlier.

In his classic 1969 book The Emerging Republican Majority, Kevin Phillips remarks on the uncanny fact that since the early 19th century, partisan electoral coalitions had held steady and then collapsed and shifted every 36 years. 1824 to 1860, 1860 to 1896, 1896 to 1932, 1932 to 1968. That was one peculiar data point among many others in support of the thesis of his book, which was that the victory for Nixon’s 1968 campaign (for which Phillips worked) marked the beginning of the next 36-year cycle—one in which the Republican Party would reign supreme, supported by a raft of new voters, many of whom would switch over to the GOP after having briefly voted for Wallace.

Instead, the realignment was knocked off its stride in 1974, initiating a six-year interregnum of national confusion and discontent, only to reconstitute itself six years later, when Reagan managed to initiate a new era in American politics. Just as Eisenhower helped to consolidate the New Deal era of ascendent liberalism during the 1950s, so Bill Clinton did the same for Reaganism in the 1990s by pronouncing midway through the decade that the “era of big government is over.” Barack Obama and the briefly sizable Democratic majorities he enjoyed after winning the presidency in 2008 managed to (barely) pass the Affordable Care Act, seemingly breaking the rules of Reaganism (with a plan originally hatched by a then-Reaganite think tank). But the Democrats were rewarded with the biggest midterm loss in the House in 62 years, showing that the Reaganite rules still held.

Until 2016, that is—exactly 36 years removed from 1980.

Our Interminable Interregnum

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Notes from the Middleground to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.