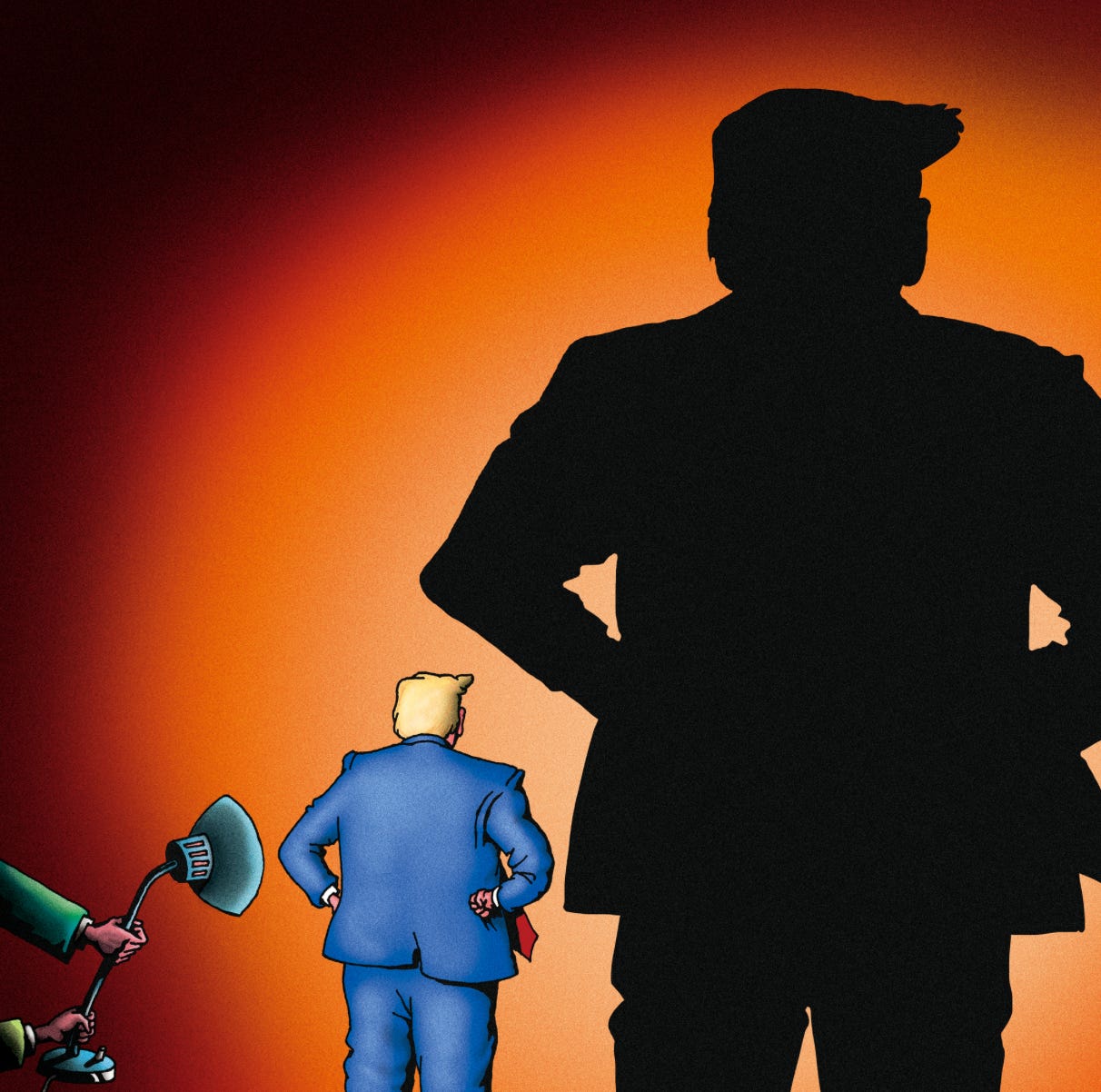

"These Thinkers Set the Stage for Trump the All-Powerful"

That's the title of my latest guest essay in the New York Times

Amidst everything else going on over the past month or so, I’ve been working on a piece of writing that appears in Sunday’s New York Times. It’s a look at a tradition of right-wing thinking about the need to enhance executive power. It begins like this:

With a blitz of moves in his 100 days in office, President Trump has sought to greatly enlarge executive power. The typical explanation is that he’s following and expanding a legal idea devised by conservatives during the Reagan administration, the unitary executive theory.

It’s not even close. Mr. Trump has gone beyond that or any other mainstream notion. Instead, members of his administration justify Mr. Trump’s instinctual attraction to power by reaching for a longer tradition of right-wing thought that favors explicitly monarchical and even dictatorial rule.

Those arguments—imported from Europe and translated to the American context—have risen to greater prominence now than at any time since the 1930s.

Mr. Trump’s first months back in office have provided a sort of experiment in applying these radical ideas. The alarming results show why no one in American history, up until now, has attempted to put them into practice—and why they present an urgent threat to the nation.

The tradition begins with legal theorist Carl Schmitt and can be followed in the work of the political philosopher Leo Strauss, thinkers affiliated with the Claremont Institute, a California-based think tank with close ties to the Trump movement, and the contemporary writings of the legal scholar Adrian Vermeule. …

I hope my subscribers will follow this gift link so they can read the rest of the piece.

One brief thing I want to add here that I don’t explicitly spell out in the op-ed: What’s typically called unitary executive theory is primarily about the president asserting power over the executive branch in a vertical way. Trump’s claim to possess the power to hire and fire executive branch employees as he sees fit, like his denial of their independence from presidential will, can be described as applications of that theory, which has been around since (at least) the Reagan administration.

But Trump has also been seeking to elevate the executive branch over the legislative and judicial branches of the federal government. He’s done this by refusing to enforce the law banning TikTok (which was passed by Congress, signed into law by Joe Biden, and deemed constitutional by a 9-0 Supreme Court decision), by claiming the power to impound congressionally appropriated funds, by defying judicial rules and expressing contempt for federal judges and courts, including when it comes to permitting due process to noncitizens marked for deportation. All of that can be described as a horizontal assertion of power that denies the doctrine of separate co-equal branches of government in favor of executive supremacy. (I’m relying here on a distinction drawn by Jack Goldsmith in his interview with Ross Douthat. I wrote about that interview in a post I published a couple of weeks ago.)

It’s primarily in the latter assertions of power that the tradition I’m writing about in today’s op-ed comes into play. The people I highlight genuinely believe that politics at its peak involves great statesmen looking out at the world, sizing up the situation (often deemed an emergency requiring decisive action), and making singular, unimpeded life-and-death decisions about what it will take to preserve the polity against an existential threat. That’s a justification for absolute executive governance.

Thanks for reading and supporting my work. I’ll be back with a new post in a few days.

Very much enjoyed the op-ed. In it's clarity, it brings back the conundrum I find most bizarre in the reasoning of these thinkers. How do you have a philosophy invoking moral and intellectual greatness and eternal truth as your compass points, posit that the crux of politics is a single man as the crucial linchpin (“the most competent and most conscientious statesman"), and then emerge at the end with . . . . Donald J. Trump?

How do you convince yourself that a trajectory of ancient Greek sages, Enlightenment philosophers, Jefferson's vision, and Lincoln's wisdom is a history that is waiting for someone so amoral and stupid? Don't you defeat your own argument?

Even if you see Trump more or less as a placeholder for the conscientious statesman, doesn't it still undercut the whole edifice of your theory of effective politics that this confused, ignorant, disinhibited person is at the pinnacle?

I get why lots of people are turned off by the tepid, constrained nature of liberal politics. But these sorts of thinkers reinforce my suspicion of their worship of "greatness." I love human excellence, too. But thinkers like this make it harder to swallow that they actually believe in something large-souled when they invoke the "great." Hard not to think something else is the psychic impulse, like a hatred of the noble/ignoble ordinariness of all humans (feelings that easily merge with disgust for women, poor people, and others who are deemed to embody the ignoble). Something bizarre has happened if you venerate Lincoln and then cheer for the venality and rank corruption of Trump and his crew.

Out of curiosity, I decided to visit the Claremont Institute's website. What a scary place it is--very white and very male; neither viewpoint nor racially diverse, which is hardly surprising given its mission both to support the current regime and to provide an intellectual foundation for its actions (and for those of future "conservative" governments). Doing so requires a lot of what I've come to see as "re-righting" American history to fit their ideology and to bury parts of the American story that don't align with their particular and peculiar vision. In that regard, they are not unlike the folks at Hillsdale College, another bastion of far-right conservative intellectual development, whose thinkers hold a major grudge against the Progressive Era. Indeed, many of the scholars and fellows at the Claremont Institute have connections to Hillsdale.

Browsing through the Institute's publications, one finds the usual defenses of Trump era policies--John Eastman on the unconstitutionality of birthright citizenship, Alex Petaks explaining the wisdom of Trump's attack on Harvard, Kevin Spivak on why the radical left Democrats hate America, and so on. My favorite, so to speak, was an essay by Scott Yenor, entitled "American Culture Fuels the Gynocracy." Ouch! Yenor concludes with the following dig at women who don't view marriage and motherhood as their primary purpose in life:

"The place of the university in the drama of a young lady’s dreams is poisonous for America’s culture and politics. But destroying the universities will not destroy the New Girl Order. The universities are not feminist factories—American culture itself is that feminist factory. Only an alternative vision of the heroic feminine can win the day."

These guys, and their few female colleagues, aren't just looking to justify the expansion of presidential authority, but to re-right American culture to fit with their vision of a mythical, patriarchal past, where folks didn't stray from their role in the hierarchy. No thanks.