Too Big to Fail: The Taylor Swift Experience

Her third sold-out stadium show in Philly demonstrates one imperfect way to square art with the imperatives of supply and demand

Beginning with this post, I’m switching from embedding the audio versions of my posts after the paywall to inserting a voiceover at the top. If you aren’t a paying subscriber, you won’t be able to access these. But if you are a paying subscriber, you’ll be able to listen in this new format much more easily than you have up until now—within the email itself or through the Substack app. Sorry it’s taken me a while to figure out this option. You’ll next hear from me toward the end of the week with an ambitious “Looking Left” post. See you then.

As I mentioned in a recent “Great Song Selection” about belatedly discovering the music of the indie-rock band The National, I fell hard for Taylor Swift during the pandemic. I’d been aware of Swift in a big way since late 2014, when she released 1989, her fifth studio album, and its parade of hit singles completely dominated FM radio over the next year. My daughter is now old enough to drive herself to dance classes and rehearsals, but back then my wife and I would trade multiple round trips a week (sometimes more than one a day) to the dance studio—and “Shake It Off,” “Blank Space,” “Style,” “Bad Blood,” and “Wildest Dreams” were the soundtrack to our schlepping.

I was ambivalent about this music. It was maddeningly catchy, and undeniably well-written and produced. If anything, it was too perfect—as I explained in one of my favorite music-themed columns for The Week. I also found the lyrics both impressively clever and maximally irritating. The album was released when Swift was 24, and the sexual innuendo on some of the singles was fitting for a young adult. But it felt like the emotional intensity and swooning self-dramatization of the love songs emerged from the psyche of a 13-year-old girl.

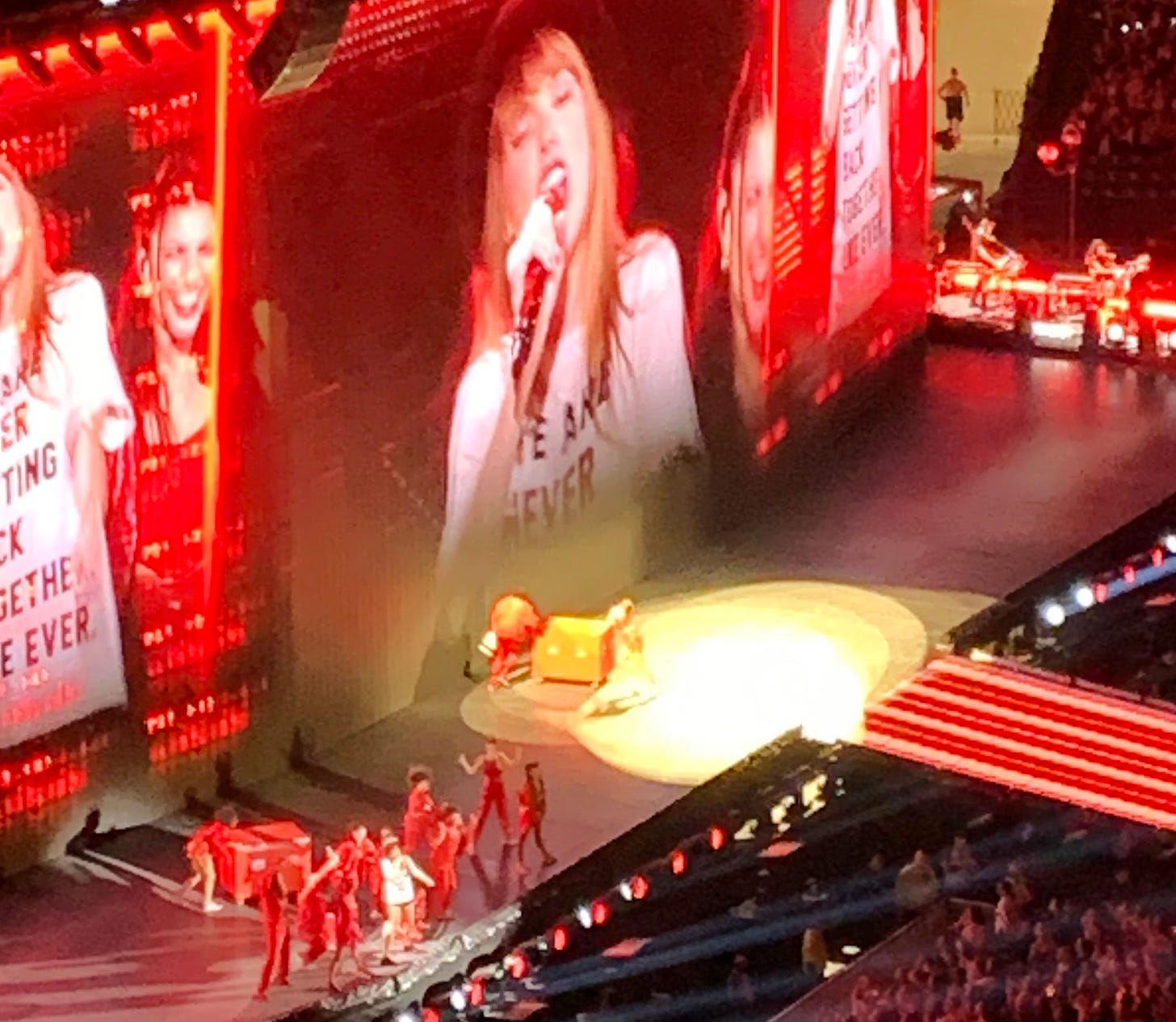

I first took my daughter to see Swift live at Lincoln Financial Field (Philadelphia’s football stadium) in 2018, when she was supporting Reputation, an album (unlike 1989) I actively disliked (with one exception). I was pretty bored at the show—though it was delightful to see my daughter having so much fun, singing and dancing along with 60,000 or so of her fellow Swifties. I liked Swift’s next album Lover a little better, but it still felt like music written from the sensibility, and aimed at the tastes, of a teenage girl. (No wonder my daughter loved it so much.)

But this changed with folklore and evermore, the two records (with 34 songs in total) she released in 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Jack Antonoff, the pop producer who left his mark on 1989, Reputation, and especially Lover, was only involved with around a half-dozen songs across the two albums. Max Martin and Shellback, the pop songwriting/production team that helped to give 1989 and Reputation their glossy, synth-based technicolor sheen, were entirely absent.

In their place, sharing songwriting and production credit on more than half of the songs, was Aaron Dessner of The National. His minimalist piano figures and subtle guitar effects created a dreamlike atmosphere on those albums that’s the polar opposite of the Adderall-infused clutteredness and hook-crammed claustrophobia of pop music in the digital age. For the first time since Swift’s early country-inflected albums, the songs were given the space to breathe rather than being smothered in overly fussy production tricks designed to get lodged in the ear like a splinter in the mind.

With overly busy arrangements no longer drawing constant attention to themselves, the melodies and lyrics took center stage, and they were wonderful. Even when writing a trilogy of songs about a teenage love triangle on folklore, Swift finally brought maturity and distance to the romantic dramas she constructed. Finally she was writing music for adults, and she was incredibly good at it (not to mention preternaturally prolific).

No One Goes There Anymore; It’s Too Crowded

The folklore and evermore albums became my family’s soundtrack to the pandemic, as they did for millions of families across the country. But this posed a problem. The pandemic forced Swift to cancel a major concert tour to promote Lover. Then, while most of the country was hunkered down at home, she released all that music that appealed to a new audience of older people like me. And because she just can’t stop writing songs, Swift released yet another album of new material (Midnights—a return to synth-based pop) in October 2022. By March 2023, a poll was showing that a grand total of 53 percent of Americans consider themselves “Swifties.” With a population of 330 million, that works out to roughly 175 million fans in the United States.

That’s an awful lot of demand—as many of us learned when tickets went on sale for the Eras Tour, Swift’s first since the last time my daughter and I attended together in 2018. I’ve gone through the process of buying tickets for high-demand concerts before. It’s pretty intense. But this time, it was a gauntlet of sign-ups for emailed presale codes, special bonus points for signing up for a credit card from Capitol One, and preferred access for people who purchased tickets for the canceled Lover tour. And then the Ticketmaster website crashed when millions of people attempted to buy tickets at the exact same time all over the country.

Somehow millions ended up with tickets to the originally scheduled shows anyway, and for the shows Swift added a few weeks later to partially meet continued demand. But I wasn’t one of them. Many cities, including Philly, ended up with three shows (though Los Angeles got five). But that was nowhere near sufficient. I get the feeling Swift could set up a three-week residency of shows in every major market in the country and sell every single ticket at every last show. She’s that popular now.

How popular? So popular that I’m ashamed to admit how much money I paid on the resale market for two lower-end-of-nosebleed tickets. To give you a hint: Tickets originally sold for between $49 and $449. When I purchased our seats, tickets on the floor that had gone for $449 (plus a hundred or so in “fees” from Ticketmaster) were selling for more than ten times that amount on StubHub. The last time I checked, those same floor seats were going for between twenty and forty times the original price. Our seats weren’t in that range—but they did cost more than the best floor seats originally did.

I suppose that means I’m part of the problem of an abundant society with a mixture of an enormous amount of disposable income and too-easily-available credit. Like roughly 200,000 people in the Philadelphia area, I was willing to spend (adjusted for inflation) something on the order of twenty-five times what my younger self spent to attend a rock concert in the 1980s and ’90s. That’s a lot of money for an experience that begins and ends in a single evening.

The Jukebox-Musical Stadium Tour

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Notes from the Middleground to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.