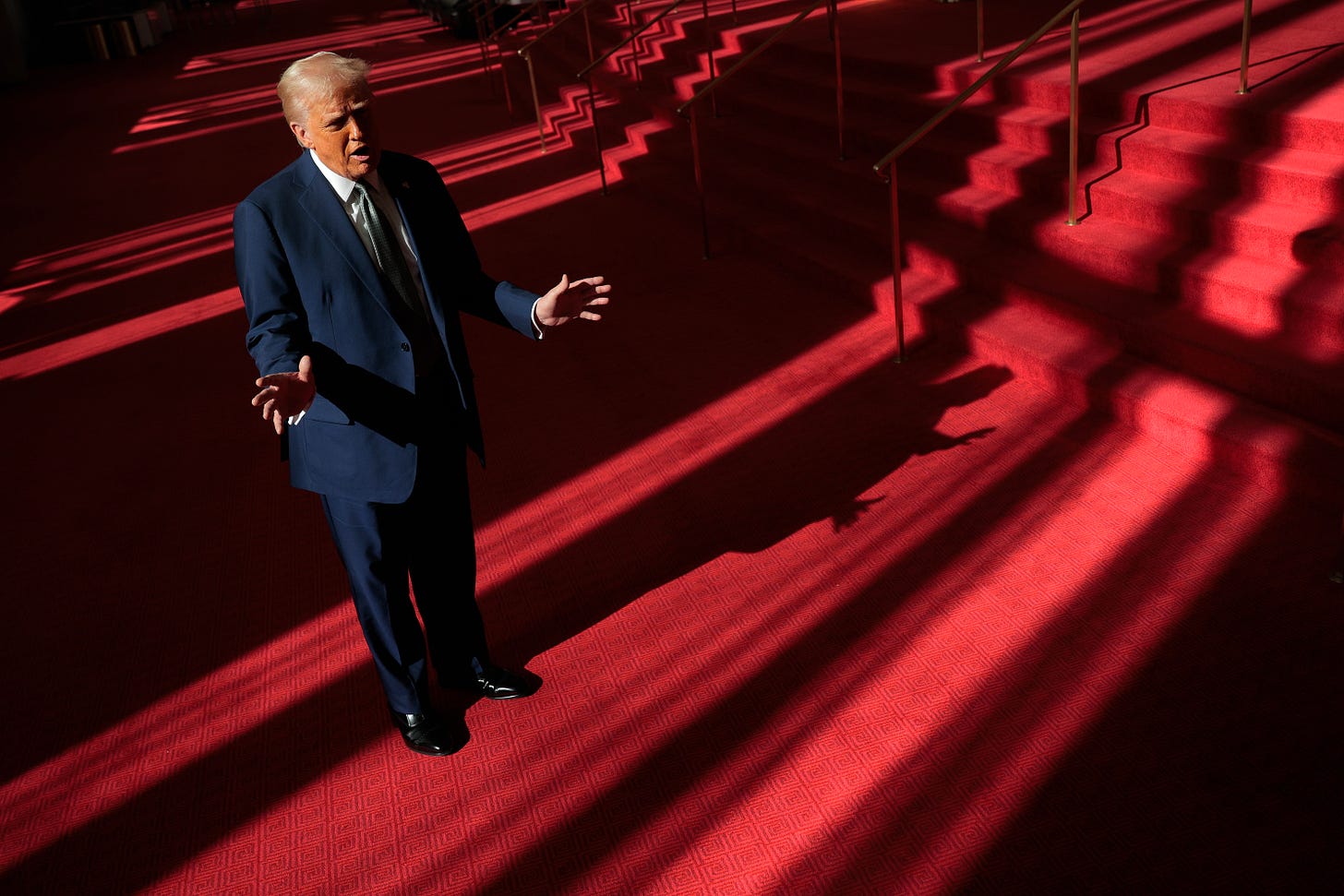

Trump Redefines the Right’s Policy Priorities

The first Trump administration sowed confusion, but the second is clarifying some of what the Republican Party will try to accomplish in its right-populist variant

Figuring out what the rise of Donald Trump over the past ten years portends for policymaking has been a challenge.

That’s because Trump is an instinctual and impulsive person, not an ideological one. He hates immigration. He favors economic protectionism. And he doesn’t believe in deploying American troops to safeguard vulnerable democracies abroad. Those are his core convictions, with just about everything else open to negotiation, and even the precise policies following from those fixed convictions left indeterminate. Then there’s the fact that during his first administration Trump had no idea how to wield the powers of the presidency and was hemmed in by his staff, most of whom were normie Republicans in the Reagan-Bush mold who were unwilling to break too drastically from presidential norms or settled GOP policy commitments.

Put it all together, and many political analysts were flummoxed. This includes opinion journalists like myself, as well as conservative policy intellectuals eager to contribute to the right-populist shift in the Republican Party. How to characterize this shift? Most agreed it involved a move away from Reaganite/fusionist conservatism (moral traditionalism, economic libertarianism, and a willingness to use military force to spread democracy and challenge its enemies). But toward what? That’s where things got confusing.

Before long, different camps formed in multiple policy areas.

Should right-populist Republicans seek to deconstruct the administrative state or seize it for right-wing ends?

Should right-populist Republicans work to transform the GOP into a working-class party by becoming friendlier to using big government social programs to benefit its own voters? A range of writers came down on different sides of this question.

And finally, should right-populist Republicans remain committed to projecting American military power into Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and East Asia? Or should we admit we lack the resources to do so much and focus above all else on the checking China and protecting our democratic allies in its backyard (especially Taiwan, but also Japan and South Korea)? Or, for a third option, should the U.S. become a free agent, cutting off all our allied dependents and redefining our sphere of influence in more limited and fluid terms?

A little more than two months into the second Trump administration, we finally have some answers to at least some of these questions.

Deconstruct or Seize the Administrative State

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Notes from the Middleground to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.