When Did the GOP Radicalize?—Part 1

A look at what Republican platforms have said about abortion since 1976 raises troubling questions about the trajectory of America's conservative party

If there’s anything the anti-Trump right, the liberal center-left, and the progressive and socialist left can agree on, it’s that the Republican Party has become much more radical in recent years.

I’m inclined to believe this as well, though I will admit that a Twitter exchange last week with conservative writer Nate Hochman has led me to re-evaluate certain aspects of this assumption. The exchange began when Hochman criticized the authors of a Washington Post op-ed for asserting that the GOP has become “increasingly extreme” on abortion. Republicans had taken the same position on abortion since 1976, Hochman asserted. That didn’t sound right to me, so I pushed back, which led Hochman to post a passage from the 1984 party platform calling for a nationwide ban on abortion.

I didn’t fess up on Twitter that night, but the honest truth is that I’d forgotten the party had taken that extreme of a position so long ago—not just committed to overturning Roe v. Wade and returning the question of abortion back to state legislatures, but also to banning the procedure nationwide by way of passing both a new amendment to the Constitution and advancing a novel reading of the Fourteenth Amendment. (This remains the maximalist position favored by Catholic integralist writers today.)

Platforms aren’t the only way to tell what a party believes in and stands for. But they are nonetheless important documents, revealing the power of different factions in a party at a given moment to demand and win private concessions and public commitments to uphold certain principles and work toward specific policy goals.

With that in mind, I’ve spent the past few days reading every Republican platform since 1976, paying special attention to the way the documents talk about abortion. What I’ve learned complicates, though it doesn’t completely undermine, my original assumptions about increasing GOP radicalization over time on reproductive rights and related issues. The platforms also raise troubling questions for Democrats about the long-term ideological trajectory of their electoral rivals—and about the political future of the country.

Partisan Sorting on Abortion Begins

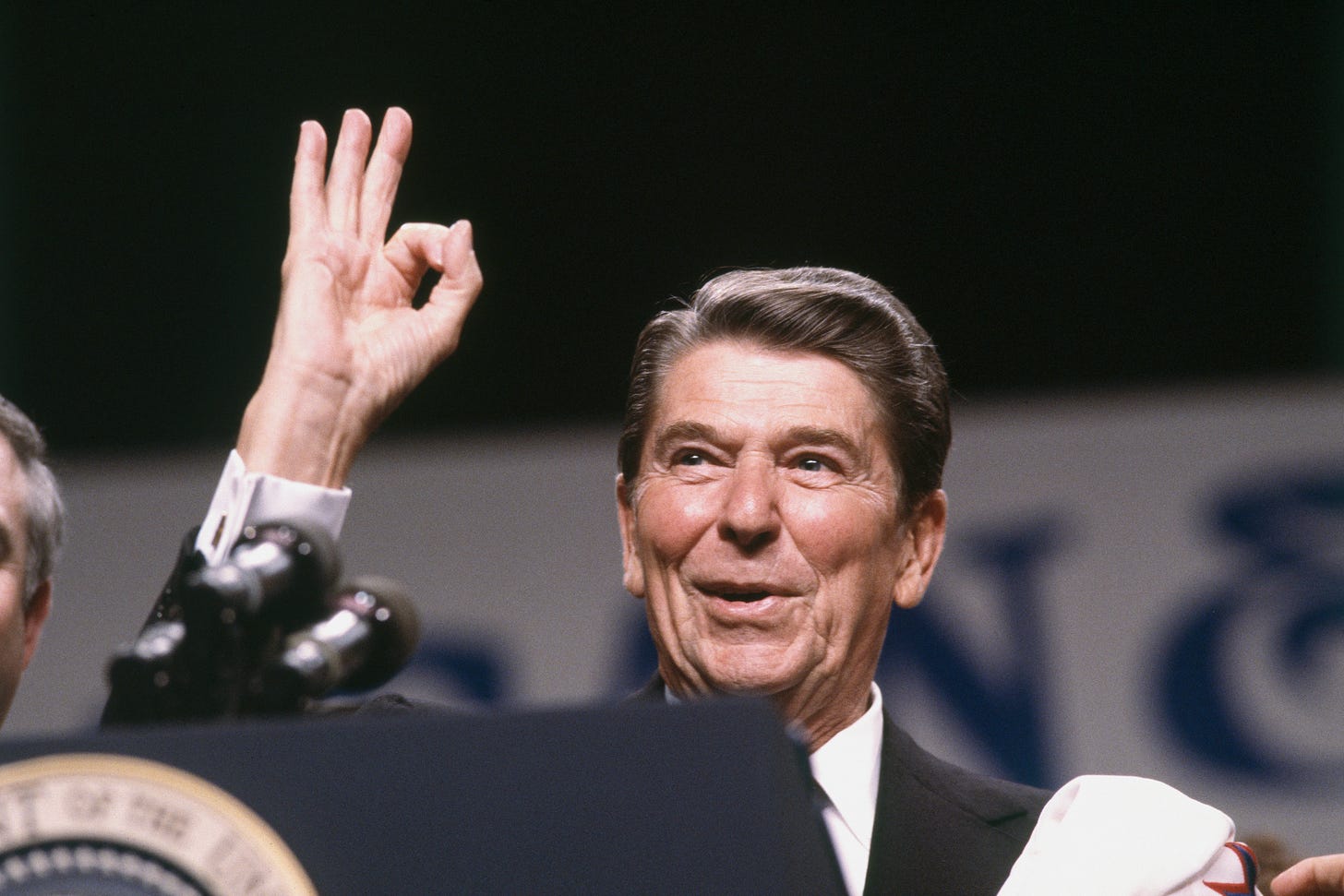

Roe was handed down in January 1973. Three years later, as the Republican Party reeled from Ronald Reagan’s primary challenge to President Gerald Ford’s bid for re-election, the party’s platform spoke about abortion for the very first time. The tone was measured, acknowledging that both the country and the party were divided by the issue. This was true. Back then, most anti-abortion voters were Catholics, most Catholics were “white ethnics” (Americans of Irish and Italian descent), and most of those voters had been casting ballots for the Democratic Party since at least the New Deal. This meant that plenty of Democrats were anti-abortion in the mid-70s.

Over the following decades, the parties would sort themselves on a range of ideologically charged issues, including abortion. The Democrats became “pro-choice,” while the GOP became “pro-life.” That process began in the 1976 Republican platform, which advocated continued “public dialogue” over abortion but also expressed support for “those who seek enactment of a constitutional amendment to restore protection of the right to life for unborn children.” Note that the document made no mention of the Supreme Court reversing Roe and returning the issue to the states, skipping right over the federalist approach in favor of a national one. That would remain the norm going forward.

From Reagan to Gingrich

It was in 1984, when Reagan was running for re-election in a contest he would win with nearly 59 percent of the popular vote while carrying 49 states, that the platform lurched far more aggressively in a pro-life direction. Now the call for a human-life amendment was paired with an endorsement for the first time of using the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause to protect the unborn child. The platform also opposed the use of public funds for abortion or “research on abortion methods,” and spoke of supporting individuals and private organizations that encouraged women to seek alternatives to abortion, including adoption.

The 1988 platform, when Reagan’s vice president George H. W. Bush was running for president, merely repeated much of the previous platform’s language. Four years after that, with Bush running for re-election, the aspirational commitments were unchanged, but the language was modestly scaled back with the rhetoric deployed somewhat more muted, no doubt reflecting the Bush 41 administration’s relative discomfort with the religious right and waging the culture war.

At the time, Bush’s loss to Democrat Bill Clinton was mainly attributed to the Republican’s aloofness in response to the recession of early 1992—just as significant congressional losses for Democrats in the midterm elections two years later were blamed on Clinton’s hapless governance during the opening years of his presidency. But in retrospect, something else was going on as well. Bush’s bid for re-election was weakened by a populist rebellion from the cultural right in the form of Pat Buchanan’s primary challenge. The rage expressed in Buchanan’s rabid speech at the 1992 Republican convention ended up helping to fuel Newt Gingrich’s successful push, two years later, to retake the House for the first time in forty years.

No wonder, then, that in the wake of this populist rebellion, the passage discussing abortion in the 1996 GOP platform was roughly twice as long as it had been previously. The document still supported a human-life amendment and Fourteenth Amendment protection for the unborn, and it still opposed public funding for abortion. But there was now more space devoted to talking about the need for judges who would “respect traditional family values and the sanctity of innocent human life.” For the first time, the document also denied the party favored “punitive action against women who have an abortion,” and spoke at length about the importance of promoting “abstinence education” and “chastity” and opposing school-based clinics that “provide referrals, counseling, and related services for contraception and abortion.”

Theocons Rising: The Bush Years

As had been the case in 1980, when Reagan was preparing his run for the White House, the platform adopted as George W. Bush was getting ready to take on Democrat Al Gore in the general election of 2000 largely mirrored the stances staked out by the party four years earlier. But four years later, with Bush 43 seeking re-election, the platform fully expressed the convictions of the coalition that stood by the incumbent president.

Now the platform contained its own subsection on abortion and related social issues titled “Promoting a Culture of Life.” As I discussed in my book The Theocons, that language was taken directly from the encyclicals of Pope John Paul II and used as a rhetorical means of bringing conservative Catholics and evangelical Protestants together in defense of a kind of right-leaning seamless garment of pro-life policies, with abortion at the core but including opposition to euthanasia, assisted suicide, fetal stem-cell research, and cloning. (Opposition to the death penalty, by contrast, was not included, for theologically dubious but politically self-evident reasons.)

The 2004 platform also praised Republicans in Congress for passing a ban on “partial-birth abortion” and the “Born Alive Infants Protection Act,” which made it a crime to refuse treatment to a fetus born alive after a botched late-term abortion. The purpose of this legislation, as I also explained in The Theocons, was to “plant premises” about fetal personhood in federal law so that a later court might make good on the party’s longstanding promise to use the Fourteenth Amendment to outlaw abortion nationwide.

The 2008 platform adopted as John McCain was preparing for his contest with Democrat Barack Obama dropped the papal language of Bush’s 2004 platform in favor of a new title for the section addressing abortion and other social issues: “Maintaining The Sanctity and Dignity of Human Life.” Other than that, little was changed that year, or in 2012, when Mitt Romney mounted an unsuccessful challenge to Obama’s bid for re-election.

Trump’s Unlikely Abortion Pledge

Which brings us to the platform drawn up in the summer of 2016, in the wake of Donald Trump’s hostile takeover of the Republican Party in the primaries that winter and spring. (That document also served as the GOP’s platform four years later, in 2020, when the party resolved to re-approve the previous platform rather than draw up a new one, citing the COVID-19 pandemic as the reason for running on autopilot.)

The first thing that stands out in the 2016 platform are the sheer number of references to abortion. From 1976 through 1992, abortion was mentioned at most half a dozen times in each party platform. This rose to around a dozen in 1996, where it stayed until 2012, when the number of mentions surged to 19. Four years later, that number surged again, to 32, with references appearing in a stand-alone section on social issues, as well as in passages covering health care, foreign affairs, and other areas of policy.

This makes the 2016 platform a particularly vivid illustration of the peculiar alignment of forces on the right that year, and since. Unlike the born-again evangelical Protestant George W. Bush, who liked to admit he received help on how to “articulate these things” from Fr. Richard John Neuhaus and other intellectuals of the religious right, Trump showed no interest in or concern with social issues, and he’d lived his life with what could most charitably be described as moral and theological indifference.

But Trump had nonetheless promised to appoint judges and Supreme Court justices who would overturn Roe, and he’d outsourced picking the right nominees to the Federalist Society. That set up a thoroughly transactional relationship with the pro-life movement. Trump made his public pledge on abortion, and the platform’s expanded emphasis on the issue appeared to show the party apparatus was ready to back him up. (The June 29th episode of the “Know Your Enemy” podcast thoughtfully discusses the transactional nature of Trump’s relationship with the pro-life movement, plus numerous other topics related to the overturning of Roe.)

The 2016 platform accordingly contained the same pledges to support a human-life amendment and fetal protection by the Fourteenth Amendment that had been made for decades, along with just about every pro-life statement ever made in past platforms. Though now the document also condemned the Supreme Court’s 2016 ruling in Whole Women’s Health v. Hellerstedt, in which the Court’s then-liberal majority ruled that a Texas law imposing restrictions on abortion placed an undue burden on women in the state seeking to exercise their constitutionally protected reproductive rights.

The document also devoted a lengthy paragraph to praising efforts by Republicans in various states to pass laws preventing abortions in which the fetus can supposedly experience “excruciating pain” and those “in which unborn babies are literally torn apart limb from limb.” The 2016 platform also included sneers at the Democrats for abandoning Bill Clinton’s rhetoric about making abortion “safe, legal, and rare”—language that was adopted in the 1990s to appeal to moderate voters and was never intended to woo absolutist pro-lifers—and at the Obama administration more specifically, for treating “abortion as healthcare.”

Trump’s Republican Party vowed never to do that, and on this, too, the GOP would keep its word.

In Part 2 of this post, which will be published tomorrow (July 6), I will analyze what the GOP’s stated policy commitments on abortion, as revealed in its platforms, tell us about the evolution (and radicalization) of the Republican Party over time. I will also pose a series of pointed questions about what the rest of the country, and especially devoted Democrats, should make of the development of the GOP on these issues over time.

The observation that platform language was taken directly from a papal encyclical shows that the entire anti-abortion movement is religiously based. I am hoping that someone can put together a law suit based on religious freedom to set a new precedent that makes abortion neutral in the eyes of the state. I don't know if you plan on addressing this in later columns, but the southern strategy pushed by Republicans since Nixon has bolstered the white supremacist movement. Welfare queens and Willi Horton were blatant attempt at instilling white hostility towards blacks. Trump took this to its flat out racist end point.

You almost certainly should do a similar review of Democrat platforms. My impression is of equal or even greater radicalization — in the opposite direction.