Postwar liberalism, emerging in the aftermath of the cataclysm of the Second World War, is distinctive in its emphasis on tragedy, conflict, complexity, difficulty, and imperfection.

In Part 1 of this post, I examined the thought of Isaiah Berlin, who developed a agonistic account of moral experience and suggested that liberal politics was best suited to respond to the tragic reality of moral pluralism—to the fact that the highest moral ideals or values conflict with one another, requiring compromises and trade-offs. The alternative to accepting the need for such compromises and trade-offs is to empower those who insist one ideal or value clearly overrides all others and justifies bloodshed in its name. (This is how Berlin understood the horrifying events of World War II and the enormously high stakes driving the Cold War in its early years.)

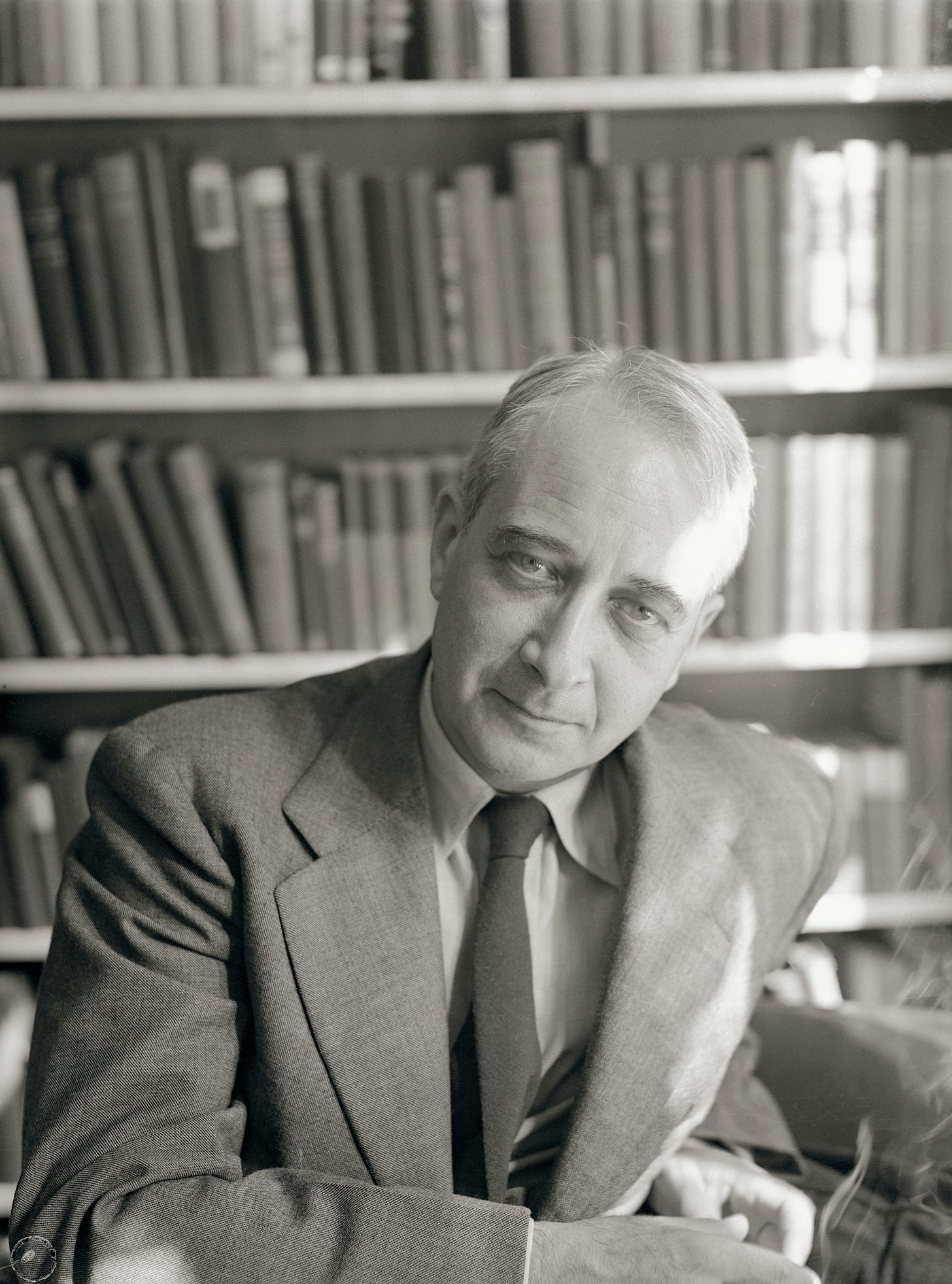

In this post, I turn to another of the postwar liberals—esteemed literary critic Lionel Trilling—in order to lay out his distinctively dialectical approach to defending and strengthening the liberalism associated with the New Deal in the United States.

A Liberal in Search of Liberal Critics

In The Liberal Imagination, Trilling insisted that the best way to fortify liberalism was to encourage liberals to open themselves and their deepest assumptions to searching criticism by non-liberals. As he put it in the famous preface of that 1950 book, “It has for some time seemed to me that a criticism which has at heart the interests of liberalism might find its most useful work not in confirming liberalism in its sense of general rightness but rather in putting under some degree of pressure the liberal ideas and assumptions of the present time.”

This is unusual. Communists don’t usually say, we will become better communists by subjecting our beliefs to criticism by non- or anti-communists. Fascists don’t seek out critics of fascism. Neither do devout religious believers typically encourage members of their faith communities to reflect critically on their own convictions from the standpoint of other religions or secular outlooks. They’re more likely to discourage such critical reflection—or, in the case of illiberal ideologies in positions of political power, to outlaw and suppress such alternative views while threatening to punish those who seek them out.

But Trilling insisted that liberalism’s greatest weakness was dogmatism about itself and its characteristic assumptions about how to govern the world. Liberalism is strengthened when it engages actively with outside criticism.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Notes from the Middleground to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.