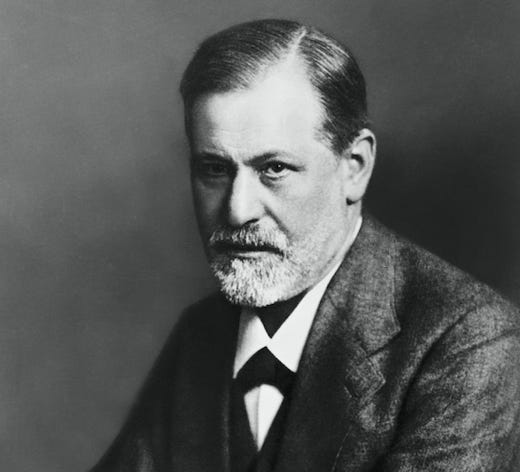

The Freud Renaissance

PLUS: For paying subscribers, on the other side of the paywall, my first Great Song Suggestion

I doubt Fridays will always be the day for “Above the Fray” posts. If there’s something big going on in the political world late in the week that cries out for comment from yours truly, I won’t hesitate to post something in “Eyes on the Right” or “Looking Left” for Friday. Yet there seems something fitting about writing less-political pieces about cultural topics just before the weekend. Hence my piece last Friday about a New Yorker profile and Oscar-winning film. And hence today’s post about the revival of interest in Freud and psychoanalysis.

In addition to the main post, today I also offer for the first time a Great Song Suggestion for paying subscribers beneath the main post, after the paywall. I’ll have plenty of occasions to write essays about new and old music here, but when I write about other topics, I will always try to include a link to something new or old I’ve been listening to lately as a bonus. This will usually be a song by a pretty obscure artist or band you might not have heard of, or else a lesser-known song by a commercially successful artist or band. I won’t go on at great length in my set-up for these links, but I will say a few things about why I chose to highlight this specific song. Sometimes, as I do with today’s selection, I will include the song’s lyrics as well. If you’re a non-paying subscriber, I’m afraid you will be excluded from this part of the newsletter. I hope you’ll consider converting to a paying subscription so you can join in the good music.

A final preliminary note: I recently joined Zohar Atkins on his consistently thoughtful podcast for a conversation he has aptly titled “Passionate Skepticism.” If you’re dying to hear me talk about Socrates, Kant, Heidegger, and Strauss (more than I already do!), including the ways philosophy connects up with having political “takes,” please do give it a listen.

And now to today’s post ….

It’s rare that I promote a cultural trend piece from The New York Times. Usually such articles strike me as faintly ridiculous efforts at extrapolating to the wider world from ideas and behavior that catch on in tony, bourgeois-bohemian Brooklyn neighborhoods but never really show up elsewhere. Instead of New York journalists generalizing on the basis of what their friends next door are saying and doing, we’d be better off reading about them less frequently and from the distanced perspective of a skilled anthropologist who normally examines the peculiar ways of isolated indigenous tribes.

But “Not Your Daddy’s Freud” by Joseph Bernstein is a rare exception. It’s good! For one thing, because it highlights something that really is a trend of growing interest in (and even fascination with) a more Freudian approach to thinking about our psyches. We can see it on TikTok and Instagram; on podcasts and TV; in magazines and film; and in the choices people are making about therapy in response to surging rates of anxiety, depression, ADHD, and other mental health issues.

Connected with this shift is a growing frustration with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) as the talk-therapy treatment of choice with which to supplement the pills (SSRIs, anti-anxiety drugs, stimulants) more and more of us are ingesting to cope with our struggles. Don’t get me wrong: CBT can and often does work. If you find yourself anxious or angry about a discrete thing (your spouse, talking to your boss, driving in traffic), CBT can help you talk yourself out of the feeling by getting you to see how your reaction to the person or situation is irrational. It can also help stop patterns of thought and behavior that can culminate in an anxiety attack or depressive episode. That makes CBT an important and powerful form of therapy.

But what if you don’t know why you’re anxious or angry? Or if you want to be happy but continually act in ways that make you miserable? Or if you find yourself incapable of giving a convincing account of how it manages to keep happening? In such cases, CBT can begin to feel like using a Band-Aid to heal a wound requiring stiches—or even one deep enough to do real, lasting damage. The over-the-counter bandage might keep things together for a while, but before long, the wound reopens. Eventually scar tissue can form, too, making healing even harder.

Freud’s Model of the Mind

That’s where Freud can be helpful. Well, not necessarily Freud himself, but the psychodynamic psychotherapeutic approaches to talk therapy that descend from him in the psychoanalytic tradition he founded. Unlike CBT, the psychodynamic approach to therapy sees human beings as strangers to themselves—unsure of what they want, self-subversive in their actions, and opaque in their motives. It therefore presumes that the obstacles to achieving happiness—which involve determining what we truly want and taking reasonable action to get it—are far greater than CBT presumes.1

This means that therapy in the Freudian tradition involves not simply listing problems and troubleshooting solutions, but making a concerted effort to achieve hard-won self-understanding. It does this by following Freud’s general model of the mind as containing sedimented layers of thinking and feeling, including a subconscious teeming with repressed images, desires, fantasies, hopes, and fears that can affect conscious thinking, acting, and feeling in strange, unpredictable ways. The mind does this by way of pre-rational forms of archaic thinking that take shape in childhood.

One example is transference, the process whereby the mind transfers associations connected with one person to another, usually of the same gender. The classic example is the tendency to experience emotions and act out unresolved conflicts from childhood over and over again with men and women in our lives who take on the roles of vicarious fathers and mothers. Depending on the nature and intensity of the emotions and the character of the conflicts, this can result in confusing feelings, skewed judgment, and fraught relationships.

Transference and other forms of archaic thinking can't be changed or stopped just by pointing to surface-level behavior and feelings and labeling them "irrational." The only way to change them is by working through the subconscious associations, emotions, and conflicts over and over again at the conscious level—in conversation with an analyst trained to look for clues of archaic thinking at work below the surface. That can be arduous, painful work; it can take a long time; and it isn’t always successful, or equally so from person to person.

A More Honest Psychology

As the NYT story suggests, this turn back to Freud after a few decades of intense skepticism is motivated by a longing to turn inward and dig deeper than CBT and other trendy forms of self-care (like mindfulness meditation) tend to encourage.

This doesn’t mean all of the criticism directed at Freud in recent years was misplaced. Some of his theories do lack an empirical foundation and seem rooted in the idiosyncrasies of his own psyche or imported from unexamined prejudices that prevailed at the time in which he lived. The latter is to be expected when reading books from the past, but it’s actually less true for Freud than for most authors. (The NYT piece notes, for example, how accepting he was of homosexuality.) But Freud’s case is unusually fraught because he so often adopted a scientistic rhetoric that overstated the explanatory power and universality of his claims. It’s as if he laid a trap for himself by insisting psychology could model itself on and achieve the same solidity of results as the physical sciences.

It's more honest to recognize that any true science of the self—any attempt by the mind (as subject) to grasp its own nature (as object)—is bound to fall short of the rigor and replicability that can be achieved when the mind works, instead, to understand purely physical processes. Put in slightly different terms, the very thing that makes each individual effort at psychodynamic psychotherapy so difficult—our lack of self-transparency—also influences the character of psychology as a collective form of truth-seeking.

The proof of psychology’s validity, as the saying has it, is in the pudding. Does a specific form of therapy help you to understand yourself, to feel better, and to make better decisions over time? If so, it has value, even if it doesn’t work for everyone, and even if the extent of (and time required to achieve) improvement varies widely.

Politics on the Couch

Then there’s the usefulness of deploying psychoanalytic assumptions to understand politics. Sam Adler-Bell, who’s quoted in the article, has done a lot of this with co-host Matthew Sitman and their guests on the “Know Your Enemy” podcast I plug so often in my posts. Using Freud to understand politics can be fruitful, especially if it’s treated as a supplement to other forms of political analysis. As Adler-Bell puts it in the piece, it might be that “purely materialist analysis of people’s motivations doesn’t give us what we need to make sense of the moment.” It’s hardly surprising, to me at least, that a political era dominated by anger, resentment, fantasies of total victory, and acts of collective retribution—not to mention political actors displaying pathological levels of narcissism and self-delusion—would find insight in a set of ideas that takes its cue from the darkest regions of the human psyche.

I would only caution that any form of political analysis and engagement that discounts what our fellow citizens say in favor of pointing to motives they supposedly conceal even from themselves is bound to be unfalsifiable. It will also run the risk of reasoning from presumed false consciousness, as the analyst claims to understand the political actor better than she understands herself. That will tend to have the effect of shutting down conversation and debate, replacing them with crosstalk and shouted accusations. We already have quite enough of both in our politics.

But as one tool in the metaphorical toolbox, Freudian concepts can be as illuminating about politics as they are about the individual mind and its miseries. If Joseph Bernstein is right that those concepts are coming back into fashion—and I think he is—it should be considered an encouraging cultural development.

Great Song Suggestion

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Notes from the Middleground to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.